(Pla2na/Shutterstock)

The Trump administration has put a price on access to China’s AI market. Nvidia can now continue shipping select AI chips to Chinese customers as long as it observes performance caps and returns 15% of those sales to the U.S. The decision replaces blanket bans with conditional permission, opening a narrow lane back into a market that makes up more than a tenth of Nvidia’s revenue.

That shift rewires incentives on both sides. Nvidia gets access to the huge market, but it must weigh margin pressure against the risk of ceding ground. The Chinese buyers face ceilings that set model size, training timelines, and deployment speed. Contracts that once focused on volume and delivery dates will now include compliance checks and performance thresholds. Other governments could follow this template and adopt similar arrangements, stacking costs and further fragmenting the global AI market.

Reportedly, Trump asked for a 20% cut of Nvidia’s China sales and settled at 15% after talks with Jensen Huang. He also signaled he would allow a China-only Blackwell that is materially toned down, on the order of 30% to 50% less capable.

This new arrangement changes the AI chip landscape significantly. It’s worth rewinding a bit to understand how we got here. Over the last two years, export controls capped raw compute at the chip and system level, and vendors learned to live inside those lines. Nvidia responded by offering H20 as a compliant H100 variant, lowering training muscle while preserving bandwidth for responsive services.

(Source: Rokas Tenys/Shutterstock)

The tradeoff provoked a broader argument. Was this smart containment that preserved oversight, or a loophole that kept China’s AI projects moving? Regulators tightened their grip, then froze licenses, and the tug-of-war moved from engineering to policy.

Buyers adjusted by stitching together capacity from U.S. clouds, domestic silicon, and whatever legacy stock they could source. Schedules slipped, costs rose, and every choice carried a compliance checklist. That was the backdrop for the turn you just described.

Last month we reported how the market had adjusted. Nvidia added a 300,000 unit H20 order at TSMC to an existing buffer near 600,000 to 700,000 units, shifting from reliance on inventory to fresh production as China demand firmed. Major buyers in China had already placed large requests, but licensing remained in process.

This arrangement crafted by Trump’s administration is unusual. It links market access to a continuing payment, which is not how export controls typically operate. The legal debate turns on characterization. If the 15% is viewed as a tax on exports, the Export Clause becomes a serious barrier. If it is treated as a regulatory fee that supports oversight, the analysis shifts to fit under the Export Control Reform Act.

Beyond legality, the structure sets a policy precedent. Expect Congress to demand the underlying legal analysis, the audit plan, and the accounting rules for funds collected, while industry asks for clarity on dispute resolution, sunsets, and how “covered transactions” are defined.

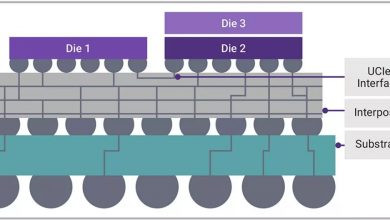

The licensing corridor maps cleanly to three chips. The H20, which is the present workhorse, is configured to respect ceilings while serving dense inference and moderate training. B30A is the next step, a China specific Blackwell positioned near half of B300 compute and still awaiting approval before any samples move.

RTX 6000D covers teams that focus on serving or local development and want to stay comfortably within the rules. This means that China can keep services running and train mid-size models on the licensed parts. Frontier-class training remains off the table, for now. Nvidia retains a presence, but only under strict performance caps, audits, and the revenue share.

RTX 6000D covers teams that focus on serving or local development and want to stay comfortably within the rules. This means that China can keep services running and train mid-size models on the licensed parts. Frontier-class training remains off the table, for now. Nvidia retains a presence, but only under strict performance caps, audits, and the revenue share.

B30A is still pending, so the lane could narrow or widen depending on approvals. If it gets approved, buyers get a clearer planning target for the next cycle. If it is narrowed or delayed, H20 remains the ceiling and substitution pressure toward local silicon grows.

As of now, the revenue share model applies only to Nvidia’s H20 and AMD’s MI308, each subject to Commerce licensing. However, the White House has signaled the model could expand, but no other firms are covered.

On the political side, reactions are mixed. Backers cast the approach as leverage that keeps frontier compute out while preserving visibility into shipments. Critics warn it blurs the line between security policy and taxation and risks hardening a precedent other countries could copy.

Senate leaders moved quickly to oppose the arrangement, warning it undercuts the intent of export controls and could run afoul of the law. As they put it in a letter to President Trump, it “the ability to sell critically sensitive technology to our adversary, blatantly violates the purpose of export control laws.”

There has been no official comment from Chinese authorities. The precedent may rankle policy makers, but leading platforms are unlikely to wait on principle. To avoid losing momentum, they will try to acquire any licensed supply while hedging with domestic accelerators and cloud rentals. Procurement teams will map workloads to the ceilings, lock in allocations, and keep options open in case approvals tighten or prices rise. It’s an unpredictable environment, so companies need to stay in the moment, keep budget headroom, and keep alternates ready across suppliers.

Related