The world is changing. Superpowers are rearming, and advanced economies are prioritizing secure supply chains. In theory Greenland could be Europe’s ace in the hole: this vast island promises the untapped natural resources the continent is sorely lacking.

In the first part of this article we covered the enormous potential for mining in Greenland and highlighted a few success stories; in this part we’ll examine the equally enormous obstacles.

High Costs

Mining in an area as remote as Greenland comes with extra costs. Greenland has very little transportation and industrial infrastructure and a limited workforce. Ore will almost certainly have to be shipped by sea for processing. Much of the power generation, port facilities, and even housing required to support a major mine will have to be built from scratch. Staffing a large mine would likely require hundreds or even thousands of foreign workers – this could mean major demographic changes for Greenland’s ~57 000 residents.

Climate comes into play in many ways. Long, cold winters make for short field seasons and sea ice may restrict access to more northern areas. Severe cold takes a toll on people and machinery alike, leading to higher costs for heating, fuel, and maintenance. Retreating glaciers expose new land for exploration, but these tend to be unstable and prone to landslides.

Greenland Supports Mining… In Theory

With dreams of independence dependent on developing a sustainable economy, Greenland’s government claims to welcome mining. Over the last ten years or so Greenland has openly courted foreign investment, including from Chinese firms many as western governments have been treated with suspicion. These efforts have yet to pay off.

At least part of the reason for this lack of investment is that Greenland’s resource policy is not friendly to mining. Greenland has a complex tax and royalty system which taxes different commodities at different (and generally very high) rates. Not only does this further increase costs, in the case of mines producing multiple elements it also increases uncertainty and complexity in navigating the tax system.

While surveys indicate most Greenlander’s support mining in theory, many have also opposed specific projects once they’re proposed. Concerns about mine wastes contaminating the sea, upon which the Greenlandic lifestyle and economy have depended for centuries, have proven hard to put to rest.

In 2021 Greenland banned the development of oil and gas resources for environmental reasons. A separate law passed the same year banned mining any deposit containing more than 100 ppm uranium. Mining of radioactive materials was previously banned from 1988-2013.

Recent elections have seen the center-right Democrats replace the former left-wing Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) government. The Democrats are considered pro-business and have supported mining; whether this will lead to a change in policy remains to be seen.

Case Study: Kuannersuit

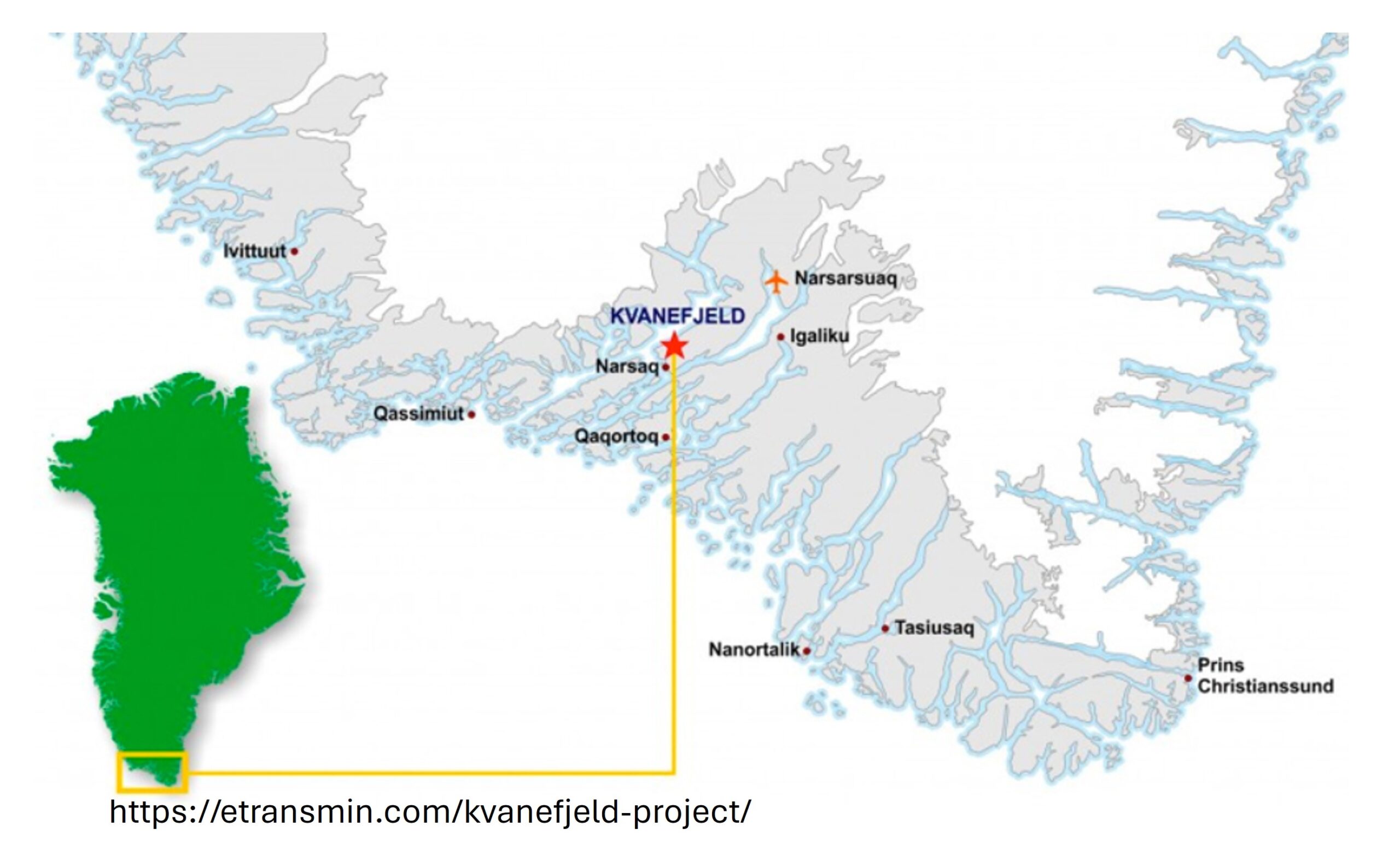

Kuannersuit (AKA Kvanefjeld), is the world’s second largest Rare Earth Element (REE) deposit and sixth largest uranium deposit, with total proven and probable reserves of 108 Mt at 1.43% Total Rare Earth Oxides (TREO), 362 ppm U3O8 (uranium-oxide), and 0.26% zinc and measured, indicated and inferred resources of 1.01 Gt at 1.1% TREO, 266 ppm U3O8, and 0.24% zinc. The light REEs make up about 96% of the total REE resources. These figures include the Sørensen and Zone 3 satellite deposits. The project is owned by Energy Transition Minerals (formerly Greenland Minerals).

Kuannersuit is part of the 1.16 billion year old Ilímaussaq alkaline complex, which also hosts the Tambreez REE project. The deposit occurs at surface and is zoned, with the upper region hosting mineralization mainly in the complex phosphate mineral steenstrupine [Na14Mn2+2Fe3+2Ce6Zr(Si6O18)2(PO4)6(PO3OH)(OH)2•2H2O], while the deeper areas host some mineralization in silicates as well. Open pit mine life is estimated at 37 years.

The Kuannersuit REE Project seems like exactly the kind of opportunity Greenland is seeking. The project would’ve generated hundreds of jobs and ~$220 million in revenue, about 7% of Greenland’s GDP, while helping Europe meet its REE needs. Unfortunately, it would have also produced uranium.

Kuannersuit is located in a sensitive area near Greenland’s only farmland, and concerns about radioactive mine wastes stoked local opposition to the point that the future of the project became a central issue in Greenland’s 2021 election. The IA won and promptly followed through on its promise to ban uranium mining, effectively killing the project.

Needless to say, Energy Transition Minerals (ETM) was not happy. The company had invested $10’s of millions on drilling and bulk sampling for the project. They also applied for an exploitation license in 2019, which appeared to be progressing but had not been granted before the ban came into effect.

As far as ETM is concerned, the abrupt change in policy amounts to unfair interference and the company is now suing Greenland for $11.15 billion, almost 4 times Greenland’s GDP. This astronomical figure includes costs, lost revenue, and interest. Energy Transition Minerals is not footing its own legal bill, this is being covered by Burford Capital, a litigation finance specialist that will receive a portion of the settlement if they win the case. A major decision on whether the case moves forward is expected later in 2025.

Bad Policy, Bad Outcome

Kuannersuit provides a rather bleak example of the reality of mining in Greenland.

There’s plenty of unanswered questions about the project itself: as is often the case with REEs the problem is processing rather than mining. Steenstrupine has never been processed at scale before, and there’s reason to doubt the ETM’s claims that the REEs can be easily extracted. Most ore minerals contain two or three elements; steenstrupine contains nine (and probably more with substitutions). The company only expects to recover about 50% of the uranium, an element which is typically much easier to extract than REEs. Even assuming extraction has been solved the fact remains that the project would overwhelmingly produce light REEs, which are much less desirable and supply threatened than heavy REEs.

The matter of radioactive waste also needs clearer answers. The tailings would contain about 150 ppm uranium. This is well above background (a granite countertop might contain 5-25 ppm) but still poses very little health hazard except possibly in the case of dust being inhaled. What is more concerning is that little mention is made of the radioactive element thorium. Thorium is less radioactive than uranium, but is far more common, especially in REE minerals like steenstrupine. Uranium may be a red herring compared to thorium, but with so little publicly available data on it in Kuannersuit it’s hard to know how hazardous the mine waste would actually be.

Valid concerns aside, Greenland’s uranium mining ban is simply resource policy at its worst. Great strides have been made in managing toxic mine wastes, and there’s no obvious reason why these risks couldn’t be managed in Greenland the way they are at dozens of uranium mines around the world today. Greenland’s uranium mining ban leaves no possibility of reaching such a solution. Even if the ban were overturned, the history of flip-flopping suggests that it could still be reinstated before the mine could enter production. Long-term stability is essential for an industry where timeframes are increasingly measured in decades.

The 100 ppm uranium threshold for the ban is both arbitrary and self-destructive. Most REE deposits contain some uranium, and the cutoff chosen by Greenland is low enough to effectively ban most REE mining. Iron-Oxide-Copper-Gold (IOCG) deposits often contain more than 100 ppm uranium, so base and precious metals are impacted as well. Add in the ban on fossil fuel extraction and Greenland has taken a large portion of its natural resources off the table.

The chilling effect of such heavy-handed action should not be underestimated. Radioactivity may get disproportionate attention, but all mines produce environmental impacts and may spur controversy. Greenland is already a risky and expensive place to mine, throw in a government that might ban an entire industry for political reasons, and it starts to become clear why the investment Greenland needs to achieve full independence has been slow in coming.

Greenland is one of the most heavily climate change impacted regions in the world: the irony of it banning extraction of resources needed for clean energy is the cherry on top of a veritable feast of self-defeat.

The lawsuit could also have far-reaching consequences. It’s not unreasonable for the company to seek compensation for its stranded investment, but the amount they’re seeking could bankrupt Greenland. It’s far from certain how much money, if any, ETM will actually receive, and in all likelihood Denmark would end up paying the bill, but many third world countries would struggle to pay such an enormous settlement if they in such a situation. Similar lawsuits are becoming more common around the world; a large payout to ETM could set a precedent that would make changing and enforcing resource policies much more costly.

This might seem like a win for the mining industry, but it may actually harm the industry’s long-term interests. If revoking or denying approval for an advanced project becomes too costly, governments may decide it’s safer to shut exploration down before it gets started.

Takeaways

Tapping Greenland’s vast resources is a bit like nuclear fusion: it’s been at least 10 years away for at least 10 years. Harsh climate and lack of infrastructure presents obstacles, but Greenland’s mining policy may be the larger issue. Complex tax law and restrictive bans on energy commodities make mining even more difficult. A history of bans being overturned and reinstated for political reasons creates uncertainty and discourages investment. With a new government taking over the future of the massive Kuannersuit Project, and mining in Greenland in general, is once again in question. Unlocking Greenland’s mineral wealth will be a long, complicated process requiring both major investment and political support.